With an increased focus on controls (and their effectiveness) from regulators, boards, auditors, and other stakeholders, can you demonstrate that your key controls are operating as intended?

Many organisations are guilty of having controls on their risk register but not doing much else with them aside from waiting on the risk to crystalize or for an incident to happen that will flag the ineffective controls? Taking this approach, how can you be sure that your controls are working as intended?

What is a Control?

There are many definitions out there but for now let us focus on the ISO 31000 definition that a control is a measure that is modifying risk.

Many organisations choose to categorise their controls, and below are just a few of the examples that we have seen:

- Preventative Controls – These controls are designed to prevent undesirable events from occurring. Examples include Segregation of Duties and Systems Access Rights.

- Detective Controls – These controls are designed to identify issues / errors that have already occurred. Examples include Reconciliation of Bank Accounts and System Access Log Reviews.

- Corrective Controls – These controls are designed to correct / resolve an issue that has already occurred. A good example of a corrective control would be Carrying out Key System / Data Backups.

Control Testing

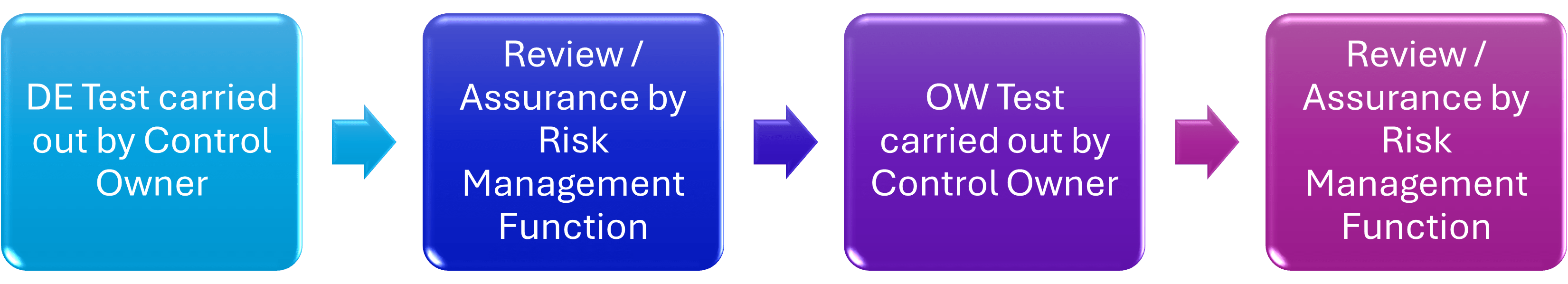

Organisations take different approaches to the actual testing of their controls; our opinion is that it is best to break the process up into two separate ‘tests’.

The first test is to check for Design Effectiveness (DE). The purpose of the DE test is to ensure that the control is appropriately designed to mitigate the intended risk(s). If the control is deemed as “Effective” following the DE test, the control owner should then move onto the Operating Effectiveness (OE) test.

The OE test involves checking if the control is operating as designed. From our experience, many controls that pass the DE test go on to fail the OE test.

In the following example, we have assumed that all testing is carried out by the Control Owner and that an independent review is conducted by the risk management function. The process may differ from organisation to organisation.

Design Effectiveness Testing

As explained above, the purpose of the DE test is to ensure that the control is appropriately designed to mitigate the intended risk(s). For organisations starting out on their control testing journey, we suggest using a simple, consistent questionnaire for each control. Here are some examples of the questions you could include in your DE test:

- Evidence – Is there a documented procedure (or other document) that outlines how this control should operate?

- Key Person – Do you have an adequate number of people trained in how to operate this control?

- Control Type – If all the steps in the control are followed, will the issue it was designed to address be prevented, detected, or corrected?

It is ok for some of the questions to be “Not Applicable” for every single control.

Once the DE questionnaire has been completed, the final step is for the Control Owner to rate the control as “Effective” or “Not Effective” (the terms you use will be determined by the scale / rating system adopted by your organisation).

There is no magic formula as to how many questions need to be answered “Yes” for the control to pass the DE test, this is something that each organisation will need to determine.

If the control passes the DE test, move onto the Operating Effectiveness test. If the control has failed the DE test, there’s very little value in testing whether or not it is operating as intended, considering that you’ve just discovered that the control is not appropriately designed to mitigate the intended risk!

Operating Effectiveness Testing

As explained above, the OE test examines whether the control is actually operating as designed / intended and this is done by “sampling” the control.

Sampling involves the Control Owner looking for examples of where the control has been operated and then testing / checking if it operated as intended. Essentially, the Control Owner is checking whether the control is operating as outlined in the DE Test results.

“How big should my sample be?”

You could link the required sample size back to the control frequency. For example, if the control operates daily / continuously, you may require the control owner to obtain twenty samples of the control from the last quarter. Whereas, if the control operates monthly, you might decide that three samples over the last twelve months is enough. Again, this will differ from organisation to organisation, and depend on the length of time you want to commit to control testing.

Conclusion

Control testing is very often missing from risk management programs, mainly because it can be viewed as very time-consuming. We feel that by following the approach outlined above, you will be able to semi-automate your control testing program and turn it into a business-as-usual activity. By doing this you will be demonstrating to your board, regulators, and other stakeholders the robustness of your risk management program.

____________________

If you are interested in learning more about how CalQRisk can help with Control Registers, Control Testing and more, click here to contact us.